PHOENIX – Sen. Carlyle Begay (D-7) stood up at the Senate Committee on Commerce, Energy and Military this week and defended his bill, SB 1098. He listed 10 reasons why Arizona needs a state film office.

The reasons must have been persuasive because after he spoke, the committee unanimously passed the bill.

That’s just the first of many battles for Begay as he tries to get his film office bill passed. The bill would create a Governors Office of Film and Media as an agency that would promote filmmaking in Arizona, and coordinate with other agencies to assist in production. The bill was triple-assigned to committee, meaning that Begay will have to repeat his speech at least twice more. But if the bill makes it into the budget, then Arizona will have a state film office again after six years without one.

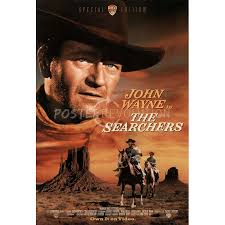

Speaking of movies made in Arizona, Begay knows the scene. He grew up on the Navajo reservation, the site of Monument Valley at the northeast corner of Arizona and southeastern Utah, the vast sweep of desert, mesa and buttes that was a spectacular setting for many great Western films, including “The Searchers,” a 1956 movie that depicts John Wayne as a Civil War veteran attempting to find his niece, who is with an Indian tribe.

“My grandparents, my parents would always watch a lot of westerns, and were very proud of that being something that was filmed in our backyard,” Begay said.

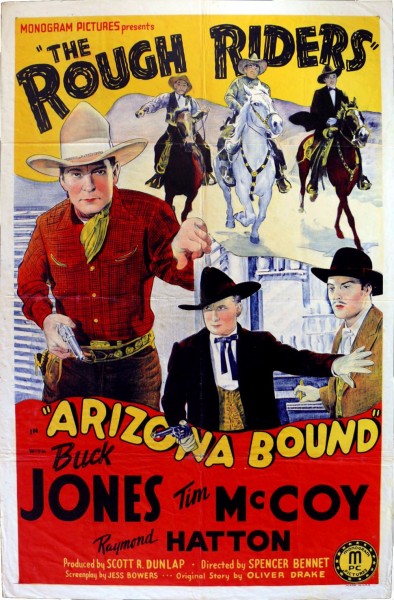

All over the world, Arizona is known for western movies that used the state’s magnificent scenery as their locales. Many people who have never set foot in Arizona know what the state looks like, thanks to movies like “Fort Apache,” (1948) and “Stagecoach” (1939), and the famous cowboy actors like Clint Eastwood and John Wayne, and directors like John Ford.

“We were the location for the western when it was in its heyday, from the 1930s through the 70s, I would say,” said Sherri Hall, the director of the Tucson Film Office, which would work with a state office if one is reestablished. “We had actors walking the streets of Tucson, staying at the Arizona Inn, and working down in Santa Cruz County.”

Cities and tribes throughout Arizona have film offices, but there is no central entity to handle the calls when filmmakers aren’t sure where in Arizona they might want to shoot. Without a central agency, many filmmakers assume that Arizona isn’t serious about moviemaking.

“Without a film office, production companies looking to shoot in Arizona do not see us as being open for business,” Hall said, “They don’t think we have the resources that they need. If we’re not professional enough to have a film office, why should they waste their time in Arizona?”

Southern Arizona was the location for television shows and a large number of movies over the years, including “High Chaparral”(1967-71), “The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” (1957), “McLintock” (1963), and “Tombstone” (1993). Much of that production activity was assisted by a state film office.

Arizona was one of the first states in the nation to have such an office, according to Hall, and for the first 11 out of her 15 years as director, she could work with a state office to help unify the efforts.

“It really helped me bring more business here,” Hall said. “We worked hand- in-hand many times, because the leads for projects would come straight to them first and then they would send that lead out to us, or whichever parts of the state were appropriate for it.”

Typically, producers will call a state film office with an idea in mind. They might need a location to shoot a scene and need to know if the state not only has that type of location, but is willing to provide assistance, like tax credits.

“When we go to another city or another state to shoot, the first thing we do is we call the film office,” said Randy Murray, owner of Randy Murray Productions. “So when we’re spending money in California or in Nevada or New Mexico, that’s where we start our process.” The production company is a boutique firm based in Phoenix that used to receive tax credits, when Arizona had such incentives. Arizona’s program for tax credits expired in 2010.

Film or television production companies also might need to find out how to get a permit to shoot on a state highway or in a state park. A state film office would field these questions and assist in production.###

“If a company were thinking about relocating their factory to Arizona they would call the Office of Economic Development and ask the same types of questions,” Murray said. “This factory is just smaller.” A movie shoot, he noted, is “only going to last for a couple of weeks or a couple of months.”

Murray runs a mom-and-pop shop of sorts. He already knows whom to call when he wants to make a film — but most big, out-of-state producers don’t.

“I know it is preventing people from coming here,” Hall said of the lack of a central state office.

In “Almost Famous,” a 2000 movie starring Kate Hudson that won an Oscar for best screenwriting, the band in the story goes on the road, visiting multiple states. According to Hall, the filmmakers used Arizona’s diverse scenery to recreate most of the U.S. states. Hall says that kind of project couldn’t happen if the state doesn’t have a film office to coordinate with, say, the Department of Transportation.

“Basically we’re missing out on business that wants to come here that’s right next door, mostly in Los Angeles,” Hall said.

Many film agencies have been skipping over Arizona and heading to New Mexico, where there is both a state film office and a program for tax incentives. One of those films was “The Lone Ranger,” a 2013 Disney movie that had a budget of over $200 million. That production had started building sets in Arizona, but when state tax incentives expired, the producers headed to New Mexico and only shot short portions of the film in Monument Valley, according to Mike Kucharo, a producer, director and former president of the Arizona Production Association.

The old state film office was disbanded in 2009. Even after the office was cut, volunteers stayed to answer the phones, Kucharo said. But that became too much and eventually the film office activities ceased.

Film incentives are tax breaks for the film industry in order to get them to film in a state. Similar to business incentives, their purpose is to attract the industry to the state and create jobs and revenue from their presence.

Since the expiration of the film tax credit and the closing of the film office, moviemaking in Arizona has languished. Old Tucson, a theme park that includes an studio complex where sets are designed like the Old West boomtown, used to generate significant revenue from film and television production. Last year, Old Tucson only brought in two feature films. Those two films, “Hot Bath an’ a Stiff Drink” and its sequel, a Hot Bath an’ a Stiff Drink 2, generated $3 million in direct revenue, according to Hall.

“With the loss of the film business, Old Tucson has been finding ways to reinvent itself and keep itself relevant,” Hall said, “It used to be that 100 percent of their business was just being a film location. That was it.”

Old Tucson isn’t the only place that suffered. The Phoenix Film Office has reported its annual economic impact since 1990. In 2013, the Phoenix office brought in $13.7 million in revenue, but in 2004-05, before the year before the film credit went into effect, the Phoenix office had brought in $10 million more. The highest yearly revenue, during the film-credit years, was $54.4 million, meaning that in 2013 had almost a 75 percent decrease in revenue.

Hall believes that, with a state film office, the Tucson Film Office could double current revenues. Last year, the Tucson film office had only $10 million in revenue, and a lot of that was from commercials and other local short productions.

The state film office was cut, in part, because of the belt-tightening during the recession.

“I think you need to make sure without multipliers that it was a net neutral or a net positive in our budget,” said Rep. Ethan Orr (R-9). Orr said he thinks that a tax credit could work, but the one that expired in 2010 wasn’t productive enough.

This time around, there is no tax incentive to lure production, and only a $612,500 yearly budget for operating the proposed state office. Begay said that some legislators are fundamentally opposed to a film office because of a belief that it represents big government.

“Many of the members here, especially those that are against that concept, feel that this should be an industry- or association-led initiative, meaning that it shouldn’t be the role of the government to create an office, to staff an office and to be a centerpoint for the industry,” Begay said.

What helped convince Begay of a film office’s worth was a trip to his district to see the making of a documentary about Navajo code-talkers. He said that the production spent more money in a hotel in three days than the hotel would typically have made in two weeks.

“For me it’s tourism, it’s hotels; it’s restaurants; it’s gaming — these are all the byproducts of this industry. For my district, which is largely rural, we rely on tourism as a big part of our economic base.”

For others, like Kucharo and Murray, it’s about preserving the grand tradition of filmmaking in the state.

“The industry has been here before the state was even a state,” Kucharo said, “There were production companies literally based in Arizona. They lived here, they worked here, and they made movies here.”

Murray wants to capitalize on that history, and make use of the landscapes that made the fundamental landscape of classic old Western movies.

“I’ve had actors run across the same plain John Wayne did. It’s an incredible history that we have in this state of filmmaking and it’s a shame not to further it,” Murray said.

Hall said she thinks that after a film office is created, there will be a revival in filmmaking in Arizona.

“Our state is a character in the films,” she said “We’re dramatic. It’s just money that we’re letting drive right through the state.”