When you think of Tombstone history you probably think of people like Wyatt Earp or Doc Holliday. You probably don’t think of Blonde Mary, Big Minnie or Madam Mustache. But you should.

Women like these were part of the social foundation of Tombstone in the late 1800s. They were business owners and working girls. But their trade wasn’t a glamorous one. It wasn’t silver mining or cowboying. It was prostitution.

Prostitution was an integral part of the building and even funding of Tombstone in its early days. In 1881, Mayor John Clum expanded prostitution, allowing it to exist in residential areas and not just in the red light district, according to a1994 book by Anne Seagraves, “Soiled Doves.” The town catered to miners and cowboys, rowdy men looking for fun. Seagraves writes that Tombstone’s “brothels were among the finest.”

Tombstone joyously celebrates its riotous history like the gunfight at the OK Corral or Helldorado Days. But it’s not so easy though to get Tombstone to come to a consensus on its history of prostitution.

This lifestyle drew some very interesting characters. Of course, there is the famous Big Nose Kate, for whom which the restaurant on Allen Street is named. Her real name was Mary Katherine Horony, and she established the first brothel in Tombstone, along with her friend Rowdy Kate.

The madams, or brothel operators, had to be tough and business-savvy. They also had to be caring towards the girls. One of the more overlooked characters was Madam Mustache, who got her name from the prominent mustache she began to develop later in life. She was a gambler, and men came from far and wide to challenge her in a card game, according to the 2005 book, “Upstairs Girls: Prostitution in the American West,” by Michael Rutter.

It was a tough town, and finding steady work as a prostitute was often the only way for a poor young girl to survive. It was a rough line of work. There was alcohol and drug abuse. Darba Jo Butler, tour guide at the Bird Cage Theatre, says there was a very dark side to the industry.

“Some of the tourists come in here and some of them make fun,” Butler said. “And when you’re that close to this building and the history in this town and stuff, you try to explain to them that 3,000 girls did not come to this town to be a prostitute. They came here to sew dresses, to look for a husband, to open a business, to do a lot of different things and unfortunately if they didn’t have somebody to support them, they were trapped.

“There was a lot of suicides, there was a lot of drug use, there was a lot of unhappiness that went along with it,” Butler said. But she says the sad stories are not what she likes to focus on. Butler prefers to think of the sense of community shown by these girls, the kindness that the women showed to each other, and their contributions to the town.

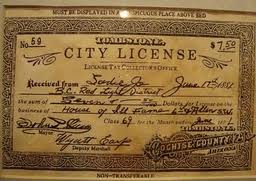

“A lot of the ladies that worked in the Bird Cage would be the first to step up to charities,” Butler said.” The money from fines for prostitution and licensing fees was collected to fund the schools, according to Rutter’s book.

Tombstone historian Nancy Sosa says she doesn’t see any record of this, but she does have records of prostitution money paying to establish the first church in town.

“I can tell you that when Nellie Cashman built the Catholic Church, prostitutes did contribute donations,” Sosa said. Sosa said her family has lived in Tombstone for over 100 years and she feels that the prostitution aspect of Tombstone may be a little overplayed. As historian, she has access to all the records of arrests, business licenses and finances. In her opinion, prostitution is emphasized now as a way to entertain tourists.

“If prostitution was truly as rampant as they say it was, we would find a lot more arrests in the docket,” Sosa said. “The myth is a lot more entertaining than the truth.”

Sosa estimated that there were probably around 37 prostitutes in Tombstone at its peak. But the true number of working girls and dubious establishments is hard to determine. Historian Hollis Cook says this is because census data did not include this information.

“We know there was at least one established boarding house,” Cook said. “And the red light district, which spanned two or three blocks east of the Bird Cage Theatre.” The district featured cribs, crudely made structures that women would rent and ply their trade out of.

Today, Tombstone invites tourists to visit the site of previous brothels, also know as “houses of ill fame.” The Bird Cage Theatre includes some information about prostitution on its historical tours. Guides at the Bird Cage say the song, “She’s Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage” was written by the composer Arthur J. Lamb after a visit to the establishment, a riotous saloon, theater and bawdy house.

“The story is that he was on the casino floor looking up at the brothel boxes,” Butler said. “He saw the girls up there with all the feathers and lace and he wrote the song right here in the bar on a napkin.” The song became a huge success and the manager of the theater changed the name from Elite Theatre to Bird Cage Theatre.

This makes for a great story but there are some logical flaws. The lyricist Arthur J. Lamb was born in 1870. The theater opened as the Bird Cage Theatre in 1881. So, Lamb would have been an 11-year-old at a bar in a whorehouse. Records indicate that the song was actually not published until 1900.

Being a crib girl was the bottom rung of the prostitution ladder — the only thing below it was a streetwalker. One crib from this time still exists. It is a small shack off Highway 80 between 9th and 10th streets.

It serves as a reminder of the conditions some women endured. “The only prerequisite a crib girl needed was to be a female,” Butler said.