By DANYELLE KHMARA

Arizona Sonora News

A year ago, Adrianne Cooper opened Cooper’s Credit Repair Nerds out of her home in Hereford, a small town in rural Cochise County, less than a half-hour drive from the Mexican border.

Within nine months, her business – helping people budget their finances and fix credit issues — moved to a 200-square-foot office in Sierra Vista, the county’s largest town. Now, she’s upgraded to a 400-square-foot storefront near a tax preparation company, a hair salon and a car dealership.

“I believe more non-traditional businesses could grow in this town,” Cooper said, who thinks the local economy these days is a lot more than just big-box stores. “It’s about the small business.”

Cooper’s success is a bit of good news in Cochise County, a hard place that has suffered more than its share of hard times. A remote, sparsely populated landscape of high desert and mountain in the far southeastern corner of Arizona – bordered by Mexico on the south and New Mexico on the east – Cochise County has watched both jobs and people flee in recent years

While Maricopa and Pima counties have largely recovered from their own economic downturns, Cochise County is still technically in recession, says Robert Carreira, who is the chief economist at the Cochise College Center for Economic Research.

Fort Huachuca, the U.S. Army base that has been at the center of the county’s life since frontier days, has seen its work force drastically cut over the past decade, falling from 13,000 jobs in 2006 to 8,000 last year.

The fort, which is a center for U.S. Army intelligence training and still accounts for more than half the county’s employment, boomed in the years after 9/11, driving local construction jobs and home building. But as defense spending went elsewhere, people moved away as well.

In 2013, Cochise had the biggest population percentage loss of any county in the nation, a 1.7 percent decline, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. From 2010 to 2015, the county had a 4.1 percent decline, Bureau figures show, declining from about 132,000 to about 126,500.

“The result was much less money in the local economy,” Carreira said. “Cochise County’s economy went into recession in 2011 and has been in recession ever since.”

The county experienced a five-year decline of gross domestic product as well, according to Carreira, which he said “easily fits most economists’ definition of an economic depression.”

Construction jobs took a huge hit – 1,700 jobs over the past decade, almost 60 percent of what Cochise had at its peak, Carreira said. And professional and business services lost 2,500 jobs in the same period.

Cochise also saw a 2015 decline in export revenue, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Although Arizona’s exports grew by $1.4 billion from 2014, Cochise exports dropped by $80 million.

The downturn is not over. The local Kmart will close its doors at the end of the year, and Hastings, another major retailer, closed at the end of October.

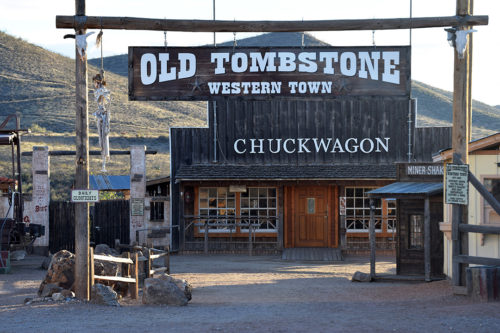

But there are some signs of green shoots in a remote landscape that helped define the American frontier in the late nineteenth century. Cochise maintains many historical sites such as 19th-century battlegrounds between the U.S. Army and the Apache, including the Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise, the county’s namesake. In Tombstone, which has also been struggling to attract new visitors, tourists can see the site of the infamous shootout at the O.K. Corral.

The Sierra Vista Chamber of Commerce received over 100 new members in the last year, said Mary Tieman, the chamber’s executive director.

“At least 30 percent of them would be brand new businesses, folks who have opened a new business in either a home setting or even store front,” she said

There’s talk within the chamber about growing more tech businesses and entrepreneurs, she said.

County officials are trying to diversify the economy and look at different options for growth.

The county’s third largest employer, Canyon Vista Medical Center, opened in April 2015 and brought 400 new jobs, according to the chamber.

Cochise College Downtown Center opened a new medical training facility in August. Eighty percent of Cochise College students graduating with degrees in healthcare find work in Cochise County and throughout Southern Arizona, Tieman said.

The University of Arizona South, in Sierra Vista, is offering a new Bachelor of Applied Science in Cyber Operations, with 20 students currently doing the on-campus program. The UA is offering an online cyber-program as well.

The community college’s medical training and the UA’s cyber security degree is going to help maintain the local work force and bolster the economy, Tieman said.

“The sector that has the potential to most effect Sierra Vista in a positive way is cyber,” she said. “That’s a growing industry.”

Cochise continues to rely heavily on the defense sector. The downsizing at Huachuca, which has a focus in cyber operations, has stabilized. They even added 82 jobs last year.

Defensive aerospace and unmanned aerial vehicles are also an important sector in Cochise, Tieman said.

But perhaps the county’s greatest hope for future prosperity is a proposed 28,000-home Villages at Vigneto retirement community in Benson, a town along the San Pedro River in the northern part of the county.

Carreira said if developer El Dorado Holdings is successful in achieving and maintaining the proposed 2,000 residential units from 2020 to 2031, it will transform the Cochise economy, “spurring unprecedented growth.”

“Even if developers fall far short of their target, that project is likely to give a significant boost to construction in the region in coming years,” he said.

In the meantime, officials and educators do what they can to bolster small business and support employees.

Cochise College also has the Small Business Development Center with assistance for potential startups such as one-on-one consulting, workshops and financing help for entrepreneurs going into the defense industry.

Cooper is teaching local youth about managing credit, doing 45- to 90-minute sessions at local high schools, middle schools and the library.

“A lot of our kids—including at middle schools and high schools—they don’t have a clue about a credit report; they don’t have a clue about credit; they don’t have a clue about paying loans,” she said. “The kids are in, utterly, shock when we talk about these things. I call these life skills.”

Simone McFarland, Sierra Vista’s economic development director, is working with the chamber to do “business walks,” obtaining information from businesses to identify where the city should be putting its efforts. With the help of volunteers, they’ve already surveyed two-thirds of Sierra Vista businesses. They knew who was hiring to find jobs for the Hastings employees affected by its closure.

“We were able to move those people that were going to get laid off into other positions,” McFarland said.

Officials also helped the Peacock Restaurant reopen. Owner Hiep Thi Wingate closed at the end of 2015, after 20 years in Sierra Vista, because her monthly rent increased by $2,500, and the building owners wanted a new deposit of $30,000, Wingate said.

“It hit rock bottom,” she said. “We were trying to survive. We were trying to get by.”

Sierra Vista Economic Development found her a more affordable site and walked her through all the required steps to reopen.

After renovating a new space, Wingate was finally able to reopen in August and was met by a large reception of locals, excited to eat her Vietnamese cuisine.

“We feel so lucky that everybody cares about us—I mean genuinely cares for us,” she said.

Wingate hopes the economy will improve, but skeptical after so many years of struggle.

“I hope to do better, but I don’t know,” she said. “We always hope for more.”

##

Download high resolution images here.