In the 1950s, Tucson was a major fashion industry player, all thanks to one garment: the squaw dress.

The dress’ skirt fans open like an accordion. Its lightweight style makes it perfect for hot summer days, but due to evolving silhouettes over time, it can often only be found in a vintage shop around town or preserved in a museum.

The squaw dress’ reign spanned nearly 20 years. Its influences can still be seen today in square-dancing dresses, proving that despite a racially tinged name both then and still today, in addition to changing styles, the dress’ wide-ranging impact never truly faded.

Though the dresses were representative of a niche market in Tucson, they exploded into mass retailers such as J.C. Penney and Woolworth’s, in addition to high end stores like Neiman Marcus.

Dr. Nancy Parezo, professor of American Indian studies and anthropology at the University of Arizona, is one of the few who has conducted scholarly research on the squaw dress’ history.

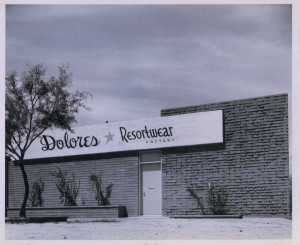

(Photo Courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society.)

She said the dress originated from Mexican and Native American full-skirted garments, such as the “broomstick skirt,” where fabric was pleated and wrapped around a broomstick to create creases. Another key feature of the dress is multiple skirt tiers, which are decorated in rickrack, the wavy ribbon-like trim that adorns many squaw dresses.

But the squaw dress is not just one dress, Parezo said. It’s actually a broad term for multiple dress styles and is often known by other names, such as a fiesta dress or patio dress.

The dress draws influences from a combination of three similar dress types, all with a big tiered skirt: a slightly gathered skirt based on Navajo dress, a “broomstick” or pleated skirt based on Navajo and Mexican attire, and a fully gathered, three-tiered skirt based on contemporary Western Apache camp dresses or Navajo attire, according to an article written by Parezo and Angelina R. Jones titled, “What’s in a Name? The 1940s-1950’s Squaw Dress.”

These one- and two-piece dresses were commonly worn at regional fiesta events, and were incredibly popular throughout Tucson as the style for University of Arizona sorority rushes and high school prom dresses, where according to Parezo, they were marketed as special occasion wear in a niche market.

The dress was one of the first regional styles in the ’50s that really defined the Southwest and exploded on the scene in Tucson thanks to local designers. But one woman — Dolores Gonzales — is believed to be one of the earliest pioneers of the dress’ impact in Tucson.

Gonzales and her brother worked together to produce these dresses locally at her factory and sell in her store.

“They’re unsung heroes,” Parezo said of these family business pairs. “We as historians need to put them back in the record.”

When the mass retailers came to Gonzales wanting to buy her dresses, according to Parezo, Gonzales turned down the offer because she would not be able to control the quality and uniqueness of her dresses if they were mass-marketed. It would also take money away from her downtown-area store on North Stone Avenue.

The impact of Gonzales’ decision not to sell to the mass retailers was profound. She was able to maintain production in Tucson and keep people, especially Mexican-Americans, employed during the ’50s and ’60s, according to Parezo. Gonzales’ work also lent to the creation of subsidiary industries such as the making of rickrack, Parezo added.

One of the reasons Tucson worked so well as a core place for the squaw dress’ appeal back then, according to Parezo, is that Mexican and Anglo citizens were accepted together better than in other communities.

“I think it’s those Mexican-American families that did the core (work),” Parezo said. “I think they’re the real key for why this worked.”

Tucson also had a strong grasp on the market due to the families’ decision to keep the quality up and not cut corners by mass-marketing, which according to Parezo, allowed the middle class to have high-end fashion, or haute couture, for a reasonable price.

Though the dress brought haute couture to the masses, with its name, also came controversy.

“Squaw” is considered derogatory, something that was of concern then and now among those who refer to it as the squaw dress instead of the patio or fiesta dress.

According to Parezo, “squaw” was originally an Algonquin word for “woman,” but over the years in English became a sexual and violently derived term toward women.

The meaning of the word changed drastically over time, and since squaw dresses are nostalgically recognized in the retro clothing market, according to Parezo, they still may have that derogatory name attached.

Debating the name misses what’s important, she said in her article, and that’s “the origin of the attire and the recognition of American Indian women’s sartorial creativity and beauty.”

Eventually, as the A-line dress came into vogue, the squaw dress went out of style. Except for the niche market of Tucson, Parezo said, where the dress stayed because it was still needed for traditional fiesta occasions in Arizona.

The style would then move out to the Midwest for square dancing, according to Parezo, and would lose its association with Tucson.

The life story of Gonzales’ work and her dresses returned to Tucson in 2015 when her story was featured at a Tucson Modernism Week exhibit, put on by the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation.

The preservation foundation chose to feature Gonzales’ dresses to look at Tucson’s effect on Southwest culture and design on broader global designs, according to Demion Clinco, executive director for the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation.

“All of the sudden, Tucson built an industry,” Clinco said of the rise of not only people appreciating the Southwest in culture, but also of the fashion that seemed to grow out of it.

People flocked to Arizona to stay for weeks at guest ranches, according to Clinco, and would purchase the squaw dresses to wear here and in their hometowns.

Men also were not excluded from the unique Southwest style, Clinco said, as they wore handmade cowboy boots and bolo ties.

“It was a time where there really was a Southwestern aesthetic, and it was in everything,” Clinco added.

Dolores wasn’t the one who helped make the squaw dress popular. Over a dozen fashion designers were working in Tucson during the 1950s fashion boom, including the late Cele Peterson, another Tucson fashion trailblazer, Clinco said.

Many other companies also sold and helped produce the dress in Arizona, such as George Fine of Georgie of Arizona, where the competition for producing the dress was fierce not only in the state, but across the country among mass retailers.

“There was a business here of fashion,” Clinco said. “The social identity of the city was these garments and they became a remarkable regional feature of our city.”

Kelly Nolan, a curator of an online Etsy shop called Cowgirl in the Sun, sells vintage squaw dresses that she finds at vintage and antique fairs around Arizona and New Mexico.

Nolan said when she attended the University of Arizona, she wore squaw skirts with other western pieces, such as cowboy boots, as did many other students.

“They were ubiquitous,” Nolan said. “They were everywhere in the ’80s.” Now, the dresses are “really hard to find,” she said.

Nolan said she didn’t know about Gonzales’ and her impact on Tucson’s fashion history until she attended the exhibition at Tucson Modernism Week, where she was in awe of the dresses.

“I think it’s important to Tucsonans,” Nolan said, calling the squaw dress “tangible evidence” of our local culture.

“I think when people from other places buy it,” Nolan said, “they are longing for this elegance — this desert elegance”

Maggie Driver is a reporter for Arizona Sonora News, a service from the School of Journalism with the University of Arizona. Contact her at [email protected]. ‘

Click here for high-resolution photos.