When it comes to primary healthcare in rural communities, Arizona is falling short of health practitioners needed.

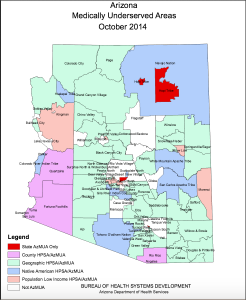

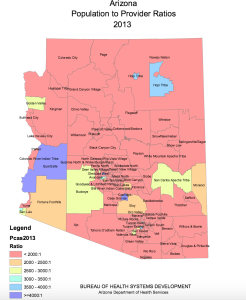

Whether they’re located in the dense forests of Northern Arizona, the broad plains of the reservations located along the New Mexico border or in the remote eastern desert of the state, rural communities are subject to the least amount of practicing health professionals per capita.

All throughout the United States, rural populations have a low percentage of health coverage and access to quality health services compared to economically thriving urban areas. Arizona’s estimated rural population in 2014 was 347,277, according to the Rural Assistance Center. Those lacking the most medical access in Arizona are the rural areas along the U.S./Mexico border and the Navajo and tribal reservations.

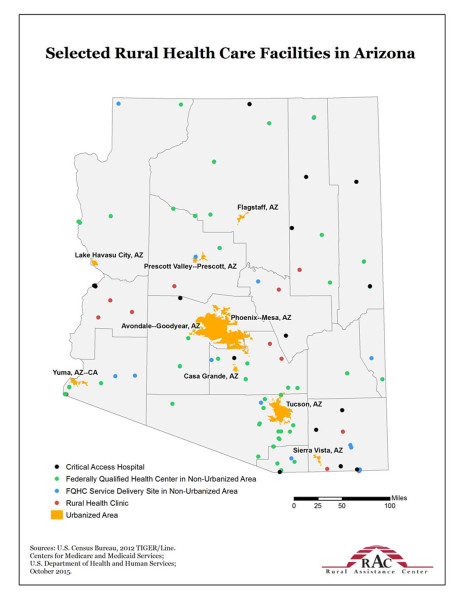

Out of the 72 hospitals in Arizona, only 20 of them are in rural communities. Additionally, there are 14 critical access hospitals (a rural hospital with 25 or fewer inpatient beds, an average length of stay of 96 hours for the patient, and 24/7 emergency services, and that is located more than 35 miles from another hospital) and 21 rural health clinics. Although this sounds like plenty of medical assistance, it still is not enough – around 91 percent of all the physicians in Arizona reside in urban areas, according to a 2012 report by the Arizona Area Health Education Centers Program (AHEC).

Many rural residents tend to be poorer than urban residents, widening the disparity between those receiving health in metropolitan areas and those in rural settings. According to the National Rural Health Association (NRHA), “on the average, per capita income [in rural areas] is around ‘$7,417 lower than in urban areas, and rural Americans are more likely to live below the poverty level.’”

Another problem in rural areas is increased travel distance and delays for emergency medical services, and many of the first responders in rural areas are volunteers, according to the NRHA. These rural communities are also more likely to recruit middle level health practitioners such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), instead of doctors.

NPs are advanced registered nurses who can provide medical care to all ages without the supervision of a doctor. Instead of attending nursing school like NPs, physician assistants attend a medical school or center of medicine. According to the Nurse Practitioner Schools, NPs are patient-centered while physician assistants are more disease-centered.

Even though many NPs are recruited for rural clinics, there is still a shortage of NPs overall. According to the WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, in 2010 there were 3,512 total NPs in Arizona, yet only 342 NPs worked in rural areas. Some of the counties in Arizona that have the lowest number of health professionals per 100,000 population are Apache, La Paz, Santa Cruz, Pinal, and Greenlee, according to a study by the Arizona Center for Rural Health.

Due to the increasing demand for more rural health practitioners, Arizona provides programs for university students to explore options in rural areas.

The Arizona Rural Health Professions Program (RHPP) is a program supported by Arizona AHEC to address the state’s healthcare shortages using the three state universities (University of Arizona, Arizona State University and Northern Arizona University). Each year, the universities choose 10 NPs along with UA medical and pharmacy students to participate in RHPP.

Dr. Christy Pacheco, director of the RHPP at the UA College of Nursing, understands rural healthcare. Pacheco is a family nurse practitioner who specializes in medically underserved populations in Northern Arizona. Pacheco lived and worked in a rural health clinic on the Navajo Reservation for six years before moving to Flagstaff. She currently provides leadership and support for UA nursing students completing mandatory clinical and course work.

“I designed my program so its open to everyone in the College of Nursing…because we have a lot of students that don’t plan on working in rural areas, but if you’re in a metro area, you’ll still have patients from a rural area,” Pacheco said. “All of my nurse practitioners are required to have a rural rotation in their clinical.”

Nursing students who want specific rural training can apply to become scholars; they have a certain number of hours in an isolated area and related courses to complete before receiving a certificate of completion. To further entice students to seek out careers in rural communities, there are state funds available to offset the cost of going to that area, Pacheco said.

The Regional Center for Border Health controls the San Luis Walk-in Clinic, a primary rural health center in Yuma County, located on the U.S./Mexico border. San Luis has a population of about 31,000; however, there are only three major health clinics in that area.

“We have a severe shortage of health professionals, especially for women with OBGYN and pediatricians,” said Amanda Aguirre, President and CEO for the Regional Center for Border Health. “It is very difficult to recruit families to come to this area…not a lot of malls or big schools or entertainment.”

To meet the demand for primary care practitioners, the San Luis Walk-in Clinic uses options to recruit foreign doctors who are being trained in the U.S. These doctors go through the J-1 Visa/exchange visitor program to eventually gain legal immigrant status. From the time of application, this process can take around three years. Though the process is long for both parties involved, it doesn’t always result in a doctor committing to that community, creating shortages of specialized medicine in that region.

“It took us about three years to recruit someone for internal medicine,” Aguirre said. “We fly people in to come and visit, give them a tour, show them housing available in area, and then we hope that they decide to come. We’ve been looking for a pediatrician for about a year now.”

The San Luis Walk-in Clinic recruits many NPs who have a link to other rural communities or who may have served in the Peace Corps working in isolated areas of the world. There is no special training for this area near the border, Aguirre said. Cross-border utilization for healthcare services happens frequently, or as Aguirre called it, “medical tourism.” Mexico often acts as a safety net for primary care since San Luis doesn’t have many practitioners, and since many dentists and eye doctors are located in California, right near the border.

Aguirre also developed a network called CAPAZ-MEX, which provides access to insurance for those who didn’t qualify for Medicaid or whose families didn’t have enough money to buy private insurance. Around 900 people sign up and renew their yearly membership with CAPAZ, Aguirre said, but there are still many left uninsured, adding to the poor economic climate of these areas.

Despite recruiting efforts and incentive programs for rural areas, most medical professionals are still attracted to urban areas. Of all the challenges in rural communities, what might prove to be the greatest obstacle yet is just getting people to work there.

Click here for more data and maps about rural health in Arizona.

Callie Kittredge is a reporter for Arizona Sonora News Service, a service from the School of Journalism with the University of Arizona. Contact her at [email protected].

Click here for a Word version of this story and high-resolution photos.