Thirty-three percent of the law enforcement agencies in the state don’t follow the law, an Arizona Sonora News investigation has found.

When sent a Freedom of Information request for an inventory of their weapons, canines and animals, aircraft, vehicles and body armor, only 49 percent of the agencies completely complied with the request. Eighteen percent offered incomplete inventories.

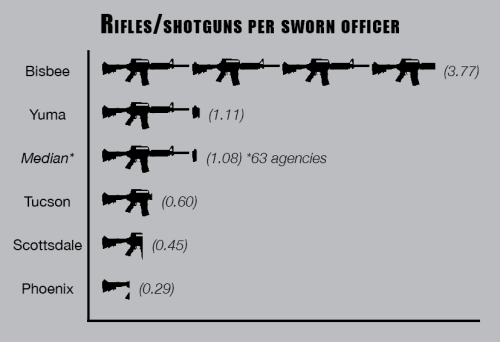

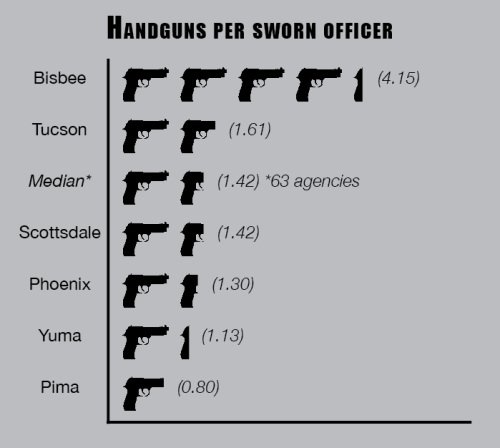

Rural communities, cities fewer than 10,000 people, are the most heavily armed. They have a median of 1.55 handguns per sworn officer and 1.8 rifles per sworn officer. The large police departments, those that serve populations over 100,000 people, have 1.5 handguns per sworn officer, but only 0.6 rifles and shotguns per sworn officer. Medium sized agencies have 1.33 rifles per sworn officer and 0.905 rifles and shotguns per sworn officer.

The median number of handguns per sworn officer, based on department’s complete inventory, is 1.42.

The median number of rifles and shotguns per sworn officer is 1.07.

The median number of less lethal weapons per sworn officer, which includes tasers and gas and beanbag launchers, is 1.21.

Public records requests were sent to 99 police departments in the state (excluding the three tribal departments that are not subject to public records law).

The request was to list all body armor, some departments gave just a total number and did no breakdowns in terms of type and quality.

Most of the departments in the state don’t have aircraft, but the big ones do. Phoenix has nine helicopters and four fixed wing planes, and the Pima County Sheriff’s office has five fixed wing planes. Tucson has three helicopters and one fixed wing airplane.

Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s Maricopa County Sheriff Office complied with our records request. However, we were not able to get the data in time to make our deadline. Maricopa County Sheriff was first contacted in September and contacted again January. Since January they were contacted three more times and responded that the request was “in process.”

Maricopa County Sheriff had their access to the 1033 program revoked in 2014 for being unable to account for 20 weapons in their 1033 inventory. Rather than deny us outright, Maricopa County stalled the process, taking more than six months on a request that didn’t take most departments more than four.

“It’s an age old thing where delay becomes denial,” said Dan Barr an expert First Amendment lawyer with Perkins Coie law firm in Phoenix. “They hope to delay the release of information long enough so that you’ll simply go away, or that the information is no longer useful to you because the news cycle is what it is.

Other departments were models of transparency. The Phoenix and Tucson police departments, the two biggest in the state, were able to provide all the information requested in a timely manner. Tucson provided 401 pages of information and inventories and Phoenix was particularly open about their surveillance equipment, revealing that they had one stingray device, a controversial device that can listen in on people’s conversations.

In terms of county sheriff offices, eight of the 13 surveyed complied with the request, they were Cochise County, Coconino County, Graham County, Mohave County, Navajo County, Pima County, Yuma County and Maricopa County.

Agencies gave a number of reasons for denying. Most claimed security concerns. Some cited the court case Pima County vs. Carlson, others Hodai vs. The City of Tucson.

“The public records laws are pretty clear,” said Jon Riches, an attorney for the Goldwater Institute, a conservative political think tank. “It says if you’re a public agency, a political subdivision in this case a department of a political subdivision, you have to disclose all information about your official duties. And then the law goes on to say that if you’re supported by public money you have to disclose public records.”

Barr said police departments have a legal obligation to share their inventories with the public.

“They’re using public money,” Barr said.

That lack of transparency can contribute to a greater mistrust between the police departments and the community, said Alessandra Soler, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona

“I think when they’re not being transparent it raises all kinds of questions about potential for misuse and for abuse,”Soler said.

Rather than looking to be transparent, some agencies will look for reasons to not disclose public information, according to Riches.

“Sometimes, government agencies get this backwards,” Riches said. “They look for reasons why they shouldn’t disclose when the law is the exact opposite. The law says you must disclose unless you can establish a very narrow reason. I think a lot of times it’s unfortunate that agencies start with the presumption of ‘why don’t I have to disclose’ when it’s the other way around.”

The most common reason for denying our request was for the safety of officers.

Apache Junction Police Department responded: “Disclosing the type of firearms and weapons our police department has to the public would present a security risk to police officers and we therefore cannot provide this information.”

Chandler Police Department was more straightforward.

“We are denying your request for weapons in the best interest of the State,” said Detective Seth Tyler in an email.

But the onus is on them.

“If the agency can demonstrate that it’s in the best interest of the state to not disclose the records, and that interest outweighs the public’s right to know, then they can attempt to rely on that exception,” Riches said. “But the burden is on the government to prove that.”

Some of the agencies focused on legal precedent to deny the request, like Bullhead City, which sent an inventory list that redacted the quantity of weapons, citing 1984’s Carlson vs. Pima County as the reason why.

“Carlson sets out, sort of a common law test in addition to a statutory reason to withhold disclosure,” Barr said. “Saying if you can show the probability of a material harm to confidentiality, privacy or the best interests of the state, then you can withhold certain information.”

However the agency that is claiming that the denial has to provide evidence that the release of the information will cause harm. They provided none.

“They have to have a factual reason for that (denial),” Barr said.

The Pinal County Sheriff’s office cited a case between Tucson Police Department and an investigative journalist named Beau Hodai, from 2014 when they denied the request.

Hodai was requesting information on whether or not the Tucson Police Department had stingray devices and the judge ruled that they did not have to reveal that information.

Despite winning that case, the defendant, Tucson Police Department, complied with the Arizona Sonora News request and provided a complete weapons inventory including the officers who carried each gun.

One of the most transparent police departments was Tempe. They allowed access to their mine resistant vehicle, as well as completely complying with the request.

“First of all it’s the law,” Pooley said. “Second of all, it’s extremely important that we don’t hide anything or even have the appearance of hiding anything. We’re a government entity and we understand that the residents, the citizens, have a right to know this information.”

Dan Desrochers is a reporter for Arizona Sonora News. He can be reached at [email protected].

For Part 1 click here.

For Part 3 click here.

Editor’s note:

This Arizona Sonora News investigation spanned over the course of seven months. It discovers alarming trends of militarization in police department fueled by government handouts and an attitude of ‘us vs. them.’ It also found a lack of oversight and training in the state.

The process began last fall with first contacting all police departments, but resumed in January with re-notifying all contacts. Around 20 percent responded by January. When all departments were later re-contacted some were still inaccessible. Sometimes the messages weren’t returned, or departments wouldn’t put us in contact with someone who was able to field the request. Some gave up the information with no fees, others charged up to $100.25.

We chose to calculate the number of guns per sworn officer because it gives a more accurate picture of the armaments of each department.

The public records law requires a department to release the information in a timely manner, which has never been formally defined. After being re-contacted in January, the majority of departments were able to meet our March 31 deadline.

Britain Eakin, a former graduate student, served as data editor managing the initial gathering of the data.

For Part 1 click here.

For Part 2 click here.

For Part 3 click here.

For high resolution photos click here.