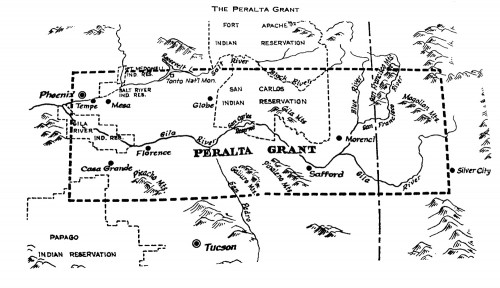

Once upon a time, the area of land stretching from Phoenix to New Mexico was part of the Barony of Arizona.

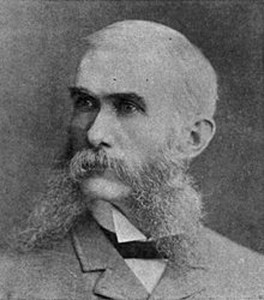

At least, that’s what James Reavis, the “Baron of Arizona,” would have had you believe.

In the early 1880s, Reavis swindled settlers in the Arizona territory, claiming he had a Spanish land grant for 12 million acres. He set up shop in Florence, opening an office for quitclaim deeds.

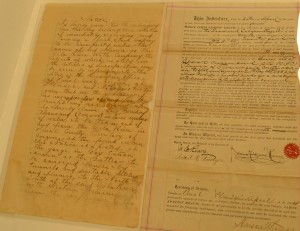

A quitclaim deed is a piece of paper that transfers a claim of land from one person to another. Reavis sold them to settlers for $25 apiece, but retained water rights.

“People were horrified,” said Lynn Smith, a volunteer at the Pinal County Historical Society. “This was early on when people were settling and to find out that they don’t own the land, that Reavis does? A lot of people didn’t have the $25 to pay him.”

Reavis even fooled the Southern Pacific Railroad, which paid him $50,000 for the right to travel through Arizona.”It was the largest land grant and largest land fraud in the U.S.,” said Jim Turner, a Tucson historian.

James Reavis originally hailed from Missouri. He got into the business of fraud during the Civil War, when he forged furlough passes.

“He was a bad boy from the get-go,” said Turner. After the war, he became a streetcar conductor and then got into real estate. There, he met a man named Doc Willing, who told him of a Spanish land grant he had gotten from a man named Miguel Peralta.

Reavis showed up in Arizona in 1880. He tried to claim the land but no one really believed him, so he created an heiress.

Sophia was a woman Reavis met by chance—some say they met on a train, or at a house where she was the maid, or at an orphanage. The only concrete thing is that Sophia didn’t have any family.

“He marries this woman and claims she’s a direct descendant of the Peralta family,” said Turner. With an heiress involved, the story seemed to have more credit.

Reavis changed his name to James Peralta-Reavis and immediately went about forging documents proving his wife’s claim and inserting them into archives.

With the money he got from swindling the populace, Reavis took his family to their “ancestral land,” Spain.

“He went to Spain and got some portraits,” said Turner. The portraits “proved” his wife’s lineage. While there, the Spanish aristocracy entertained him and his family.

Reavis thought he had proved what he needed. Everything went swimmingly for a few years, until a newspaper editor in Florence noticed something.

“He looked at the lettering and wording of these letters and realized they could be frauds,” said Smith.

At the time, the federal government was planning to pay off Reavis to leave Florence and stop his business, according to Smith. However, the editor alerted federal investigators to the possibility of forgery just in time.

“His handwriting was terrible, his grammar was terrible, and they found metallic ingredients in the ink that wouldn’t have been found in the 1700s,” said Turner.

“He wrote with a metal-tipped pen, they would have written with quills.

Reavis went to trial and was found guilty of fraud. He went to jail in Santa Fe, his wife divorced him for non-support, and he died poor.

“He was a fraud beyond fraud,” Smith said.

Gabby Ferreira is a reporter for Arizona Sonora News, a service from the School of Journalism with the University of Arizona. Contact her at [email protected].

Click here for high-resolution photos.