More than 600,000 Arizonans are affected by asthma, a controllable chronic disease, with approximately 80 deaths each year, according to the Arizona Asthma Coalition.

There are approximately 120,000 Arizonan children with asthma and every year asthma has led to 3,000 hospitalizations, costing Arizonans several millions in direct medical costs, according to the Arizona Health Sciences Center at the University of Arizona.

Compared with cancer and heart attacks the numbers are not as high, but for a condition that can be controlled the numbers are high, said Judy Harris, director of Breathmobile at the Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Breathmobile is a self-contained mobile asthma clinic that provides teaching and treatment for children with asthma.

Asthma is known to be the most common chronic disease in childhood. There are more than 6 million children diagnosed with asthma in the United States. This leads to an increase in missed school days and workdays.

The Coalition reports that approximately 1 in 10 adults in Yuma County have asthma, and data from 2001 show that 6.5 percent of children are treated for asthma annually. People who live in urban and rural areas of Arizona have also reported to be affected by asthma.

In 2003, the national rates for children who received care for asthma was 4 percent, but in Maricopa County the rates were higher at 6 percent. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that there were 14 million school days missed because of asthma.

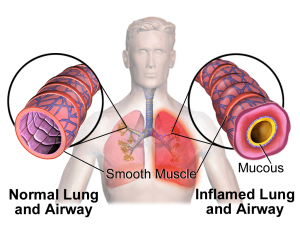

Asthma occurs when there is inflammation in the air passage that results in narrower airways that transport oxygen to the lungs. Asthma can cause chest tightness, shortness of breath and coughing, as well as periods of wheezing, a whistling sound when breathing.

A lot of uncertainty and unanswered questions remain in asthma, Harris said.

“With our research effort and technology we ought to know more about asthma but we still don’t know a lot of important answers,” said Joe Gerald, assistant professor of public health management at the University of Arizona. “The two important things we are still trying to figure out is the exact cause of asthma and why some kids wheeze early and never again or why some wheeze late.”

At a younger age, asthma is more prevalent in males than females for age 14 years and younger, but after puberty the ratios switch, and asthma becomes more prevalent in females than males.

“That is another thing that medical experts are trying to answer,” Gerald said. “Not much is known about the cause but the factors that lead to asthma attacks and how lungs are exposed is more understood.”

Asthma attacks can be triggered by irritation or allergies to dust, molds, smoking and strong odors in the environment, Harris said.

“If it’s cold weather and humidity that triggers someone’s asthma then they are going to do better in Arizona no matter what but if it’s grasses it’s not much different here,” Harris said.

The prevalence for asthma increased in Arizona from 11 percent in 2000 to 12 percent in 2003, according to the Department of Arizona Health Services. More than 390,000 Arizona adults were diagnosed with having asthma.

The average length of hospitalization due to an asthma attack in Arizona is about four days. An estimated average of $20,185 is spent on every hospitalization for a total of $650 million for all hospitalizations, according to Health Services. The majority of hospitalizations occurred among non-Hispanic White/Caucasian Arizonans and Hispanics/Latinos in Arizona.

In order to help address the issue of prevalence of asthma in children, the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona partnered with the American Lung Association in Arizona and 20 Tucson Unified Schools in the district to implement a supervised asthma program in elementary schools for the first time.

“Partnering with schools is a more efficient way to access children and ensure their attendance,” Gerald said.

The program divides the 20 schools into two groups; 10 schools are in the immediate intervention category, where the students are being evaluated for asthma control and are put on appropriate inhaled medication. The other 10 schools are in the delayed intervention category, where they are being monitored and at the end of the school year the two groups will be compared to see how many asthma incidents occurred and hospital visits.

“Hopefully what it will show is that the students’ who were placed in the immediate intervention group and their medication was being supervised by the school will have less trouble with absences,” Gerald said. “Our goal is to help students who are most at risk.”

Schools were identified by demographic characteristics that have low socioeconomic status and high minority students.

The medication is donated to the schools by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. and the inhalers remain at school to ensure that they are properly being taken and are not misplaced. This study was first conducted in Birmingham, Alabama, which demonstrated that asthma symptoms were reduced as well as school absences.

“What we are trying to do is see if such things that worked primarily in an African American setting, will it work in a primarily Hispanic/Latino setting,” Gerald said.

The program is free of charge to the students. Students who are in the delayed intervention will participate next year, Gerald said. Each student is prescribed the appropriate dosage and monitored by the school nurse.

“We think it’s a good program for both the University of Arizona and the College of Public Health mission to provide service to the disadvantaged communities but we also think it is going to do good for the kids to make them healthier, happier and more productive,” Gerald said.

—

Yara Askar is a reporter at Arizona Sonora News, a service from the School of Journalism at the University of Arizona. Contact her at [email protected].