A flippant labeling of Arizona’s Native Americans as drunks on the CBS sitcom “Mike and Molly” makes light of an issue that has long plagued the Native American communities of the state.

In early March, the television show aired an episode in which Mike’s mother, played by actress Rondi Reed, confronted her daughter-in-law, Melissa McCarthy’s Molly, about a suggested move to Arizona.

“Who the hell said I’m moving to Arizona,” Reed’s character said. “You ever been to Arizona? It’s just a furnace full of drunk Indians.”

The episode comment was followed by a faithful laugh track, but later triggered outrage from Arizona’s Native American tribes.

“This is 2013,” said Erny Zah, the director of communications for the Navajo Nation’s president and vice president. “I thought for the most part we were past a lot of these offensive slurs, not only against Native Americans, but also to all minorities in the world… ‘Mike and Molly’ is a nationally syndicated TV show on one of the big three networks…and this comment made it through to that level.”

{youtube}rjrcE6x8Vks{/youtube}

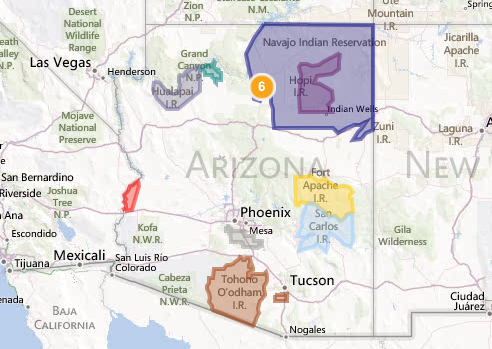

The Navajo Nation is home to the largest Native American tribe in Arizona, also stretching into Utah and New Mexico. There are 21 federally recognized Native American tribes in Arizona, and in 2011, Native Americans and Alaskan Natives made up 5.2 percent of the state’s population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Traditionally, Native American tribes are more at risk to alcohol abuse and alcoholism because of the concentration of the population living in rural lands lacking treatment facilities. Between 2001 and 2005, “11.7 percent of deaths among Native Americans and Alaskan Natives….were alcohol-related, compared with 3.3 percent for the U.S. as a whole,” said a 2008 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Roland Moore, a Senior Research Scientist at the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, has been funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, a branch of the National Institutes of Health, for several projects he has worked on. One such project was titled “Historical and Cultural Roots of Drink Problems Among American Indians,” which explored the historical roots of Native Americans and how it is a learned behavior.

“The basic story of our article was that some of the worst possible teachers of how to drink alcohol were the ones who introduced alcohol to many American Indian people,” said Moore. “Since they were the role models, that meant that people didn’t know how to drink alcohol in moderation. They thought the only way to consume it was in access.”

The U.S. National Library of Medicine defines alcoholism as a physical addiction to alcohol despite its negative effects and hold on life, while alcohol abuse involves heavy drinking but no outward signs of addiction.

“For a lot of Native Americans, this has been a social illness that has touched a lot of us,” Zah said. “This is an illness, not just a moral choice…[‘Mike and Molly’] made fun of a social illness that completely held Native Americans back for generations.”

Zah knows from personal experience the toll alcoholism can take on a person and is currently 11 years sober.

“My own experience is that those of us who label ourselves as alcoholics, our lives don’t get any better if we stop drinking,” Zah said. “[We get] more angry, more depressed and don’t have that crutch to fall on. There’s that perception that if we stop drinking, that’s all we need to do and then learn how to live life.”

An extreme prohibition of alcohol both in an individual’s life and on the reservation does not solve the problem. Even though the sale and consumption of alcohol is prohibited on most Native American reservations, alcohol addictions remain an issue for Native American communities.

“The more illegal that you make it, the more people want to go for something,” said Jean Hazen, 35, a student senator at Tohono O’odham Community College. “Just because it’s illegal, it makes it that much more fun, especially for teenagers.”

The students at Tohono O’odham Community College have experienced the draw of alcohol in their own lives, but have decided to rise above it.

The students at Tohono O’odham Community College have experienced the draw of alcohol in their own lives, but have decided to rise above it.

“I’ve stuck to my culture, and I’m staying strong with that, but I know I have a lot of friends and family members who say, ‘Oh, you should go party with us,’ and I say, ‘No, I can’t do that,’” said student senator Joeago Flores, 22. “I think it’s better to stay off of that and go elsewhere and be myself and also get a better education and a job. Because if you get influenced with that, it will mess up your life.”

Some reservations allow liquor licenses for major businesses such as casinos and convenience stores, which are exclusive to that establishment. The positive economic impact created by casinos actually funds departments and programs beneficial to reservations and the state. A major portion of these profits go toward education systems on the reservations.

In the Tohono O’odham Nation, in the southern part of the state, a $21 million grant generated by casino profits was donated to help open the two-year Tohono O’odham Community College in 2004, according to a 2012 report by the Arizona Indian Gaming Association.

This community college and other avenues of education on reservations assist in the provision of the tools necessary to help the prevention of alcohol dependence among young Native Americans.

“I’ve lived through a lot of alcoholism,” said Nacho Flores, 25, who is also a student senator. “I’ve been around it most of my life, and it has a very negative effect. It pushed me to attend school, because I see other people drinking constantly around me, and I didn’t want to be like that and be another statistic, so I decided to attend college and better myself.”

Moore thinks another solution to creating a healthier lifestyle on reservations is through having more readily available programs in the Native American communities where those struggling with a dependency on alcohol can go to get help.

“It’s certainly a lot easier if there are supportive elements of the reservation environment,” said Moore. “Including placed for healthy activities, support groups for people who are experiencing problems with alcohol, and also initiatives taken by tribal governments to reduce influence of alcohol.”

Despite research that indicates that genetics may have some influence over the potency of alcohol on an individual, social factors play a significant role in the strength of that hold, making education a key to preventing generational perpetuation of the addiction and stereotypes associated with alcohol among Native Americans.

“What we’re talking about has a long history,” Zah said. “It’s not just something we woke up to. We’ve fought for every amount of recognition that we’ve received, and it has been a long difficult road for a lot of Native American tribes, especially those in Arizona. For this show to put us in a furnace and call us drunk Indians should not be tolerated by anybody.”