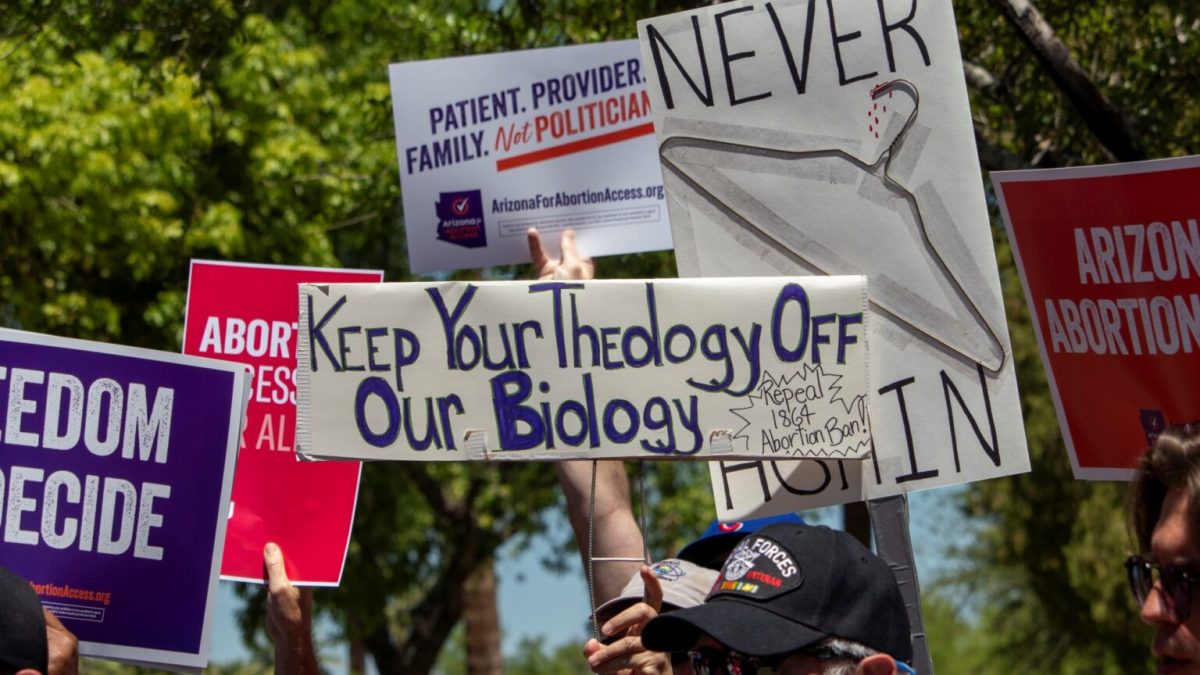

The bills create a number of barriers to care for even basic sexual health services provided by Planned Parenthood—in addition to increasing the required number of visits for an abortion and increasing medical liability for doctors and clinics who perform abortions.

The most controversial bill, H.B. 2838, included a wide range of changes to abortion procedure in the state.

Currently, women already have to get an ultrasound before an abortion, but the bill’s new requirement states this must occur 24 hours before the procedure. Critics argue this unfairly targets rural women.

Because abortion clinics are concentrated in Phoenix and Tucson, women outside those cities have to drive hours to receive abortion services. Now they would have to stretch their travel time over days—for previous visits as well as follow-up appointments.

“Introducing a provision like that in the bill is really meant to create as any barriers as possible for women to access care, especially in rural communities,” said Michelle Steinberg, Planned Parenthood Arizona’s public policy director.

But legislators stalled the passage of H.B. 2838 after concerns were raised that the bill could create a stifling climate for doctors by opening them up to crippling lawsuits.

Requirements that doctors determine the gestational age of a fetus to prevent abortions past 20 weeks calls for levels of accuracy that scientifically haven’t been reached, doctors argued. If the doctor performs the abortion past this date, a number of people besides the mother can sue—including the father or a pregnant minor’s parents.

“In a medical malpractice case, the 20-week margin can be supported and refuted by probably half a dozen medical experts on both sides,” said Rep. Matt Heinz, D-Tucson, also a practicing physician. “All of these penalties, including the revocation of licensure, are all going to stand on a very movable, uncertain, and arbitrary date which cannot be medically proven.”

This expansion of physician liability, along with a requirement that abortion clinic physicians have admitting privileges at a hospital a maximum of 30 miles away, could limit the growth of new clinics outside Arizona’s two largest cities.

“There are a limited number of hospitals,” said Dr. Eric Michael Reuss, a board-certified obstetrician/gynecologist in Scottsdale, who spoke to the committee. “It would completely decrease the ability for women outside of metro areas to have access—there won’t be enough doctors.”

Reuss explained that not all doctors have admitting privileges at a hospital, and staff at several abortion clinics agreed that for a doctor performing primarily abortions, those privileges weren’t necessary because in the case of an emergency another doctor takes over at the hospital.

Although opponents called the stalling of H.B. 2838 a small victory, it’s possible it could pop up in committee again for a vote this week.

Committee Chairman Cecil Ash, R-Mesa, said he wanted to hold the bill to further discuss the 20-week provision in more detail but he had permission from House leadership to re-introduce the bill this week.

Several bills aimed at quashing abortion in the state did pass through committee and are moving toward full consideration, including a bill that would essentially defund Planned Parenthood in the state.

This would restrict women on AHCCCS, the state’s healthcare service, from choosing Planned Parenthood as their healthcare provider because they would not be reimbursed for any service such as a well-woman exam or STD testing.

Opponents of the bill argue that this would restrict thousands of poor women with already limited access from receiving essential care.

Planned Parenthood in Arizona said of the roughly 65,000 women and men they treat each year, more than 4,000 of their patients are on AHCCCS.

“HB2800 would basically prevent Planned Parenthood from providing care to low income women using federal funding streams,” Steinberg said.

Steinberg added that abortions were just one service they provide—in addition to comprehensive STD, cervical cancer, and breast cancer screenings.

Currently, federal law states abortion monies and procedures must be fiscally separate from other family planning services. Yet the language of H.B. 2800 would restrict state funding of Planned Parenthood at all—for fear that the monies would “subsidize abortions,” proponents say.

“The concern is that by funding an organization that is providing those abortions, while a certain amount of dollars that are spent specifically on those abortions are raised privately, we are still subsidizing that organization,” said Rep. Justin Olson, R-Mesa. “We feel that public dollars should not be subsidizing organizations that offer those non-exempt abortions.”

But Rep. Heinz said restricting access in this manner would be a public risk.

“It will be a great detriment to public health and dangerous for many women,” Heinz said. Limiting the coverage of not just women but also men on AHCCCS receiving basic sexual health services at Planned Parenthood could leave them without proper treatment of STDs or access to birth control and other family planning education provided by these clinics, he said.

The women’s health debate didn’t end with these two bills. The House Judiciary Committee approved H.B. 2625, which removed the state requirement that religious employers provide prospective hires written notice that they refuse to cover all FDA-approved contraceptive methods.

Additionally, S.B. 1009 passed committee on partisan lines, demanding schools promote childbirth or adoption over abortion in sexual education programs.

Sen. Nancy Barto, R-Phoenix, said the bill was to make sex education programs in public and charter schools “consistent with Arizona’s compelling interest in protecting life.”

Heinz’s comprehensive sex education bill, H.B. 2616 requiring that districts give students medically accurate information and include discussion of contraception, never got a hearing in committee.

Steinberg says such a mentality about unplanned pregnancy and sexual health cripples the state in the long-term, because opposing abortion and promoting abstinence-only programs disregard the problem of unplanned pregnancies in the first place.

“This legislature is so completely fixated on creating barriers to abortion that they spend not minute one on solutions to these issues. What’s the bottom line? The bottom line is you want to prevent unplanned pregnancies, you want to prevent preventable diseases, you want women to have good reproductive healthcare,” Steinberg said. “So what do you do? You stop Planned Parenthood from providing family planning services. Not abortions: birth control, breast exams, cervical cancer exams, STD testing and treatment. How does this make sense?”

The debate essentially boiled down to a deep division between anti-abortion and pro-choice viewpoints—something that Steinberg and Rep. Hobbs argued would never be resolved. But the state could keep the pregnancies from happening, with proper education, they said.

“The cost to the state in unplanned pregnancies runs into the hundreds of millions,” Steinberg said.

National agencies like Advocates for Youth agree.

“In the United States we often withhold vital information or focus only on abstinence; but public health research shows that young people who receive comprehensive sex education are less likely to experience unplanned pregnancy than those that receive abstinence- only education or no sex education at all,” said Executive Director Debra Hauser. “Young people deserve honest, accurate, information to help them take personal responsibility for their sexual health. Withholding information may prove detrimental to their well being.”

Regardless of cause, unplanned pregnancies are costing the state mountains of cash. Arizona has the third highest rate of unplanned pregnancies in the nation. The state spends more than $289 million a year in public funds on unplanned pregnancies. This includes costs for prenatal care, labor and delivery, postpartum care and one year of care for the infant—according to a study by the Guttmacher Institute.

Mejdrich is a senior at the University of Arizona and is the Bolles Fellow this semester covering the Legislature. The fellowship was named to honor former Arizona Republic investigative reporter Don Bolles who was assassinated in the line of duty.