Frost stretches for miles across red dunes of the northern polar region of Mars.

But if you were to zero in on Mars’ North Pole, you would spot thousands of pits breaking up the expanse of ice and red sand – the holes are so dark that scientists cannot determine how deep they are.

The origins of these pits have also remained a mystery – until now.

As a NASA Space-Grant undergraduate Intern working with the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Science Laboratory, Dora Elalaoui-Pinedo has been studying the enigmatic pits in the northern polar regions of Mars using images taken with the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, or HiRISE, a high-resolution camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. By mapping the pits with specialized software, she explores how the pits formed and evolved to develop a better understanding of Mars’ geological activity and climate history.

Individual pit found in Mars’ northern polar region through HiRISE satellite imagery

Elalaoui-Pinedo has mapped out and located more than 2,000 pits, which she has been able to identify as round, almost circular, holes. However, she hasn’t been able to pinpoint the depth of the pits.

“Depending on whether the images are from a frosty zone or not, we can see a little crescent around the pit which shows that it’s in the ground and goes deeper into Mars’ surface,” she said.

The depth of the holes remains unknown because regardless of how the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory saturates satellite images the pits show up black. Since the pits are small – no larger than five meters in diameter – they cannot be mapped using Digital Terrain Models (DTMs), which are realistic topographical maps of Mars created with specialized software and satellite images.

“We’ll never necessarily be able to see what truly lies at the bottom of these pits. Who knows if they’re very deep or not? It’s a mystery. So, we’re here to try to use the best of our minds to work with the data that we can see,” Elalaoui-Pinedo said.

To better understand how the pits are forming, the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory team examines areas of pits over long periods of time. The team creates DTMs to analyze how the elevation might have changed in the areas surrounding the pits since frost accumulation can affect the terrain.

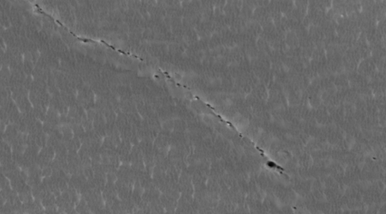

In three locations analyzed, the pits lined up in a linear fashion, proving a clue into how they might have been formed.

“When pits line up linearly, we call them fault-related pits. We believe there’s tectonic motion causing the pits to line up linearly and a sort of ‘opening’ to form on the surface,” Elalaoui-Pinedo said. “Other processes like the weather, for example, the strong winds on Mars, is another factor that might be responsible for these pits.”

Satellite image of pits in Mars’ northern polar region arranged in a linear fashion

Given how climate and geological processes relate to the formation of the pits, the project aims to establish a better understanding of Mars’ climate history and tectonic activity by examining pits that have only been found in Mars’ northern polar regions.

“We haven’t found similar pits outside of Mars’ northern polar regions, let alone on Earth – which is really exciting,” Elalaoui-Pinedo said. “Maybe we’ll be able to find a new discovery site on Earth. If not, then we’ll be able to say that the pits are unique to Mars.”

Undergraduate perspective on planetary science

Beyond hinting at details on Mars’ geologic activity, the project has also greatly impacted Elalaoui-Pinedo on a personal level.

Before starting her research on enigmatic holes on Mars through the undergraduate UA NASA Space Grant Internship, she was an astronomy major. But just as the tectonic plates on Mars shifted to form the pits, so did Elalaoui-Pinedo’s perspective on her career trajectory. During the program she decided to change her major to planetary geosciences.

“Back when I started Space Grant, there hadn’t been a specific major for planetary sciences yet, so the internship introduced me to a field that I wasn’t necessarily aware of,” she said. “It made me realize that space science is much broader beyond astronomy. So, once a planetary geosciences major was offered, I knew I had to switch because that’s the field I wanted to pursue.”

Studying pits on Mars is only the beginning of her journey as a planetary scientist, and there are few limits on what she might uncover about geological features as she continues on this career path.

“I’m planning to apply for graduate school because I’ve been really passionate about research. Especially because being a part of planetary sciences gives me the opportunity to find the answers to the great questions of our universe,” she said.

Arizona Sonoran News is a news service of the University of Arizona School of Journalism.