In the midst of back-to-back hurricanes that left thousands homeless and dozens dead in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, former President Donald Trump and his allies told supporters that FEMA was not there to help them and that the disaster relief agency was pouring its money into the welfare of undocumented immigrants.

Federal Emergency Management Agency officials scrambled to reassure hurricane victims that they could get help, but the damage was already done.

It was the latest in what has become almost the norm in American politics, to spread false information for political benefit. And some worry that the misinformation will impact the presidential election less next week.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, a liberal nonprofit law and public policy institute based at New York University School of Law, election misinformation “interferes with voters’ ability to understand and participate in political processes. And it has been weaponized by lawmakers to justify new voter suppression legislation.”

It also makes voters mistrust information they are receiving.

“It really is on us to make sure the information we are trusting is correct,” said Tyler McCusker, who teaches the100-level gen-ed class at the University of Arizona “News in Society: From the Printing Press to Fake News” for non journalism majors. “If you are uneducated, you are the most susceptible to believing fake news. If you are not used to exploring different outlets of media, and you’re not used to expanding your mind or possibilities, you can become overly confident in one source. … Fake news spreads 80 times faster than regular information.”

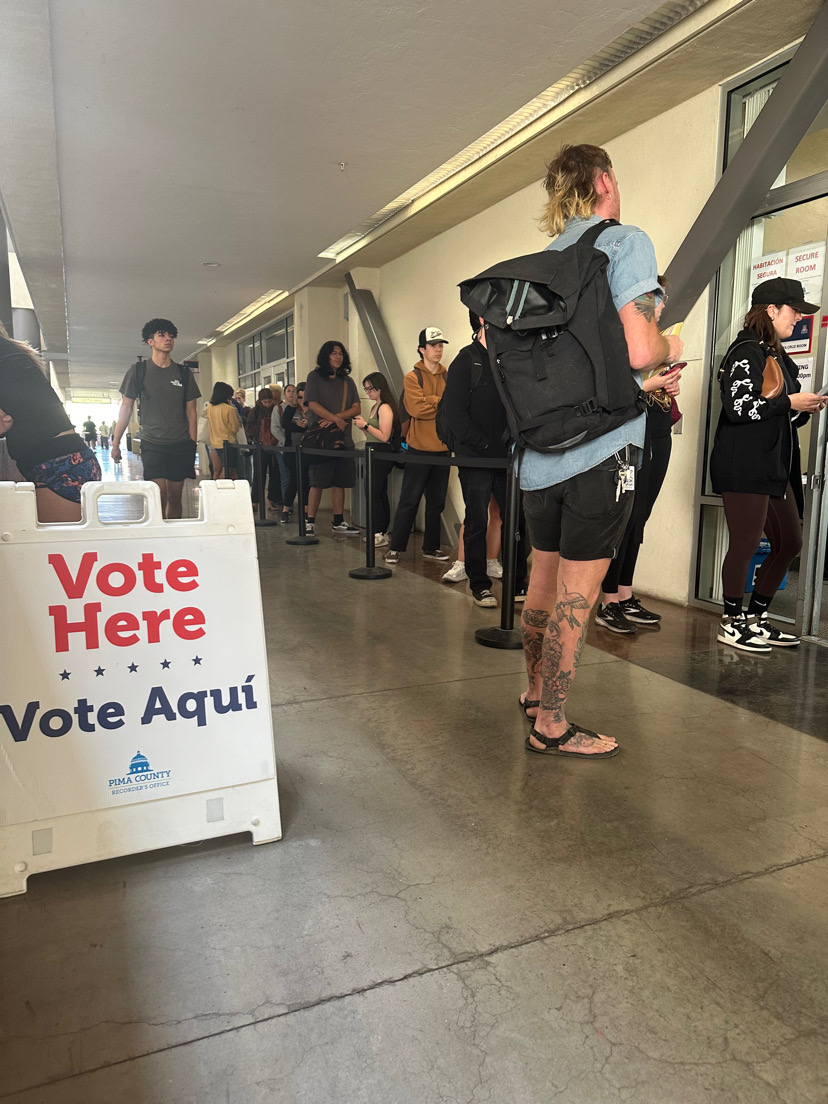

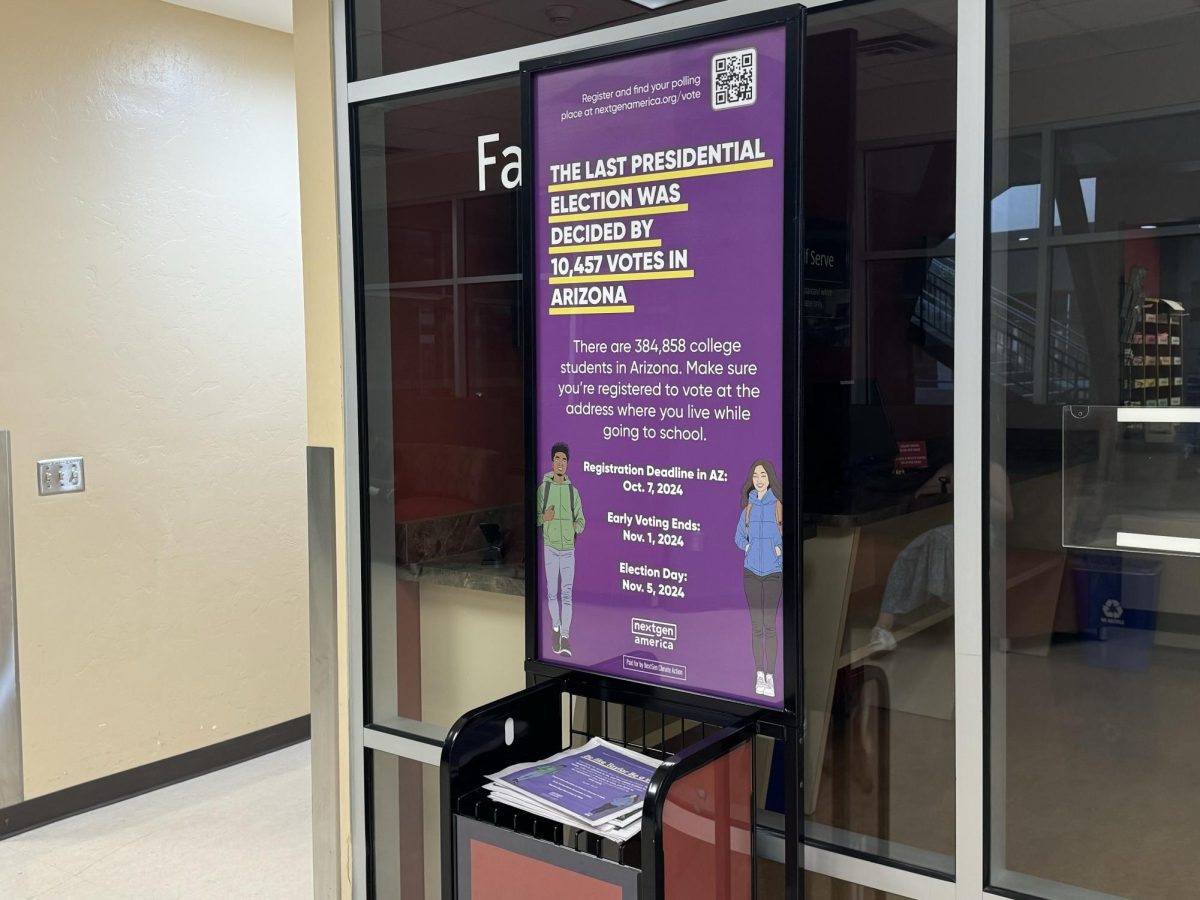

From conspiracy theories about government overreach to false claims about emergency alerts, experts warn the spread of fake news is eroding public trust as voters are beginning to cast early ballots.

This is not the first election marked by widespread misinformation about candidates’ policies or personal lives, but it has become more sophisticated in the past decade. In fact, the term “fake news” only began gaining traction on the internet and social media in the 2016 election cycle, pushed largely by Trump.

As fake news thrives during crises and change, it’s crucial for individuals, whether following hurricane updates or election coverage, to verify their sources to ensure both personal safety and informed decisions, McCusker advised..

McCusker said he hopes to equip his class with the tools to debunk poor reporting and assess the dangers of fake news.

The need to understand what news is real and relevant is heightened during a time of crisis such as the recent hurricanes.

“You’re typically going to believe the first degree of information you receive,” McCusker said. “This could be a matter of life and death.”

In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene in late September, former President Trump falsely claimed that President Biden and Washington was withholding aid from Republicans in the Southeast. He also wrongly claimed that FEMA had exhausted its funds on programs supporting undocumented immigrants, leaving no money for disaster relief.

Americans who have not sought aid due to these claims may have inadvertently put themselves at greater risk by failing to seek the help they rightfully deserve,; especially considering the unpredictable path of Hurricane Helene, which caught many people completely unprepared.

“Misinformation during a crisis is very dangerous, I think at this point people are used to being their own journalists,” McCusker said. “It really is on us to make sure the information we are trusting is correct. If you are uneducated you are the most susceptible to believing fake news. If you are not used to exploring different outlets of media, and you’re not used to expanding your mind or possibilities, you can become overly confident in one source… Fake news spreads 80 times faster than regular information.”

McCusker emphasized the importance of cross-checking information on multiple reputable sources. He also believes that age and geography, as that can influence education levels and politics, plays a huge role in who is most likely to believe fake information.

“It’s much easier to dupe a grandma than a GenZer,” McCusker said.

Social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook have implemented new measures to fact-check information and alert users when content may be misleading or false. YouTube has also taken steps to address its “fake news rabbit hole,” as McCusker described it, where the algorithm often promotes videos containing accurate information alongside those that spread falsehoods during viewing sessions.

McCusker said he had his students, who are mostly freshman and sophomores, did an exercise in class trying to debunk Trump’s recent claim that “the people are eating the cats and dogs” in Ohio. After digging, they traced the source to a local board meeting in Springfield where a member of the community claimed his cat was eaten.

Arizona Sonoran News is a news service of the University of Arizona School of Journalism.